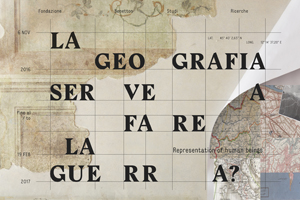

Is the purpose of geography to make war?

Representation of human beings

an exhibition of maps and art

Is the purpose of geography to make war? This is the question posed by the exhibition at Fondazione Benetton Studi Ricerche, curated by Massimo Rossi, held in the spazi Bomben of Treviso from Sunday November 6 2016 to Sunday February 19 2017, with inauguration on Saturday November 5 at 6:00 pm. The exhibition avails of the partnership of Fabrica, who curated the set-up and graphic design, and of the collaboration and patronage of the Regional government of Veneto – Council Department of Culture.

Through three closely linked layouts that remain in constant dialogue, Maps, atlases and works of art speak of the great communicative and persuasive force of geographic maps.

Maps are a powerful means of non-verbal communication and the context of the celebrations of the Great War offers a valid pretext for investigating their ability to condition public opinion when they back the point of view of the Major Nations. This is why the layout of the exhibition focuses on the historical period between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, but which actually spans from ancient times all the way to modern day, to tell the story of another possible geography and not necessarily based on military logics.

The exhibition begins with Rocks and water, where we see how maps use a simple and preemptory sign – the natural border – to turn mountains and rivers into tools that are able to separate and offer physical shape to ethnic, linguistic groups, nations to transform them into the “geographical expression” of states. The second section, Human signs, recounts the use of geographical knowledge for propagandist purposes to forcibly convey the idea of nation even before its official political proclamation. The third part, War maps, places the accent on the co-existence of two seemingly irreconcilable cultural approaches, in the context of the First world war: graphic symbols representing the vast war industry disseminated on the Piave front, along with signs that bear witness to the presence of thousands of homing pigeons that by flying at more than one hundred meters of altitude and travelling great distances in short amounts of time, inform and send orders. 305 mm mortars that discharge projectiles weighing 400 kg and as big as a man, and tethered balloons suspended hundreds of metres above the ground «swaying in the sky in a long line along the Piave» as described by writer-tenant Fritz Weber, the enemy on the opposite bank.

At the exhibition we will appreciate how the maps provide order in an otherwise chaotic world, making it more understandable and familiar, distinguishing the objects, but most of all naming the places allowing us to recognise every single one of them. In every era, as quintessential social and human products, maps have also told the story of places through toponyms, sometimes playing an aggressive power over them. Especially when they alter the original spelling of centuries-old names or replace them altogether with new ones to make them more akin to the most recent dominators: the Dutch Niew Amsterdam becomes the English New York; the German Karfreit turns into the Italian Caporetto to then become the Slovenian Kobarid; the Hapsburg Sterzing becomes the Romanised Vipiteno. Or yet, to fulfil impellent social urgencies and to give a voice to hitherto unexpressed territorial hopes: “Alto Adige”, “Venezia Tridentina”, “Venezia Giulia”, or simply, in the case of a river, by changing its gender.

The century-old Piave of the log drivers changed gender in 1918 to offer greater virile resistance to the Austrian invasion, becoming “Il Piave” (male gender), to reassure the collective imagination of the young Italian nation.

But is it actually true that the purpose of geography is to make war? Certainly, without geography wars would not even be conceivable, but man has always been the one to make war, and is willing to use all the available knowledge of physics, chemistry, geometry or mathematics to achieve his objectives.

This exhibition also looks into another possible geography, a geography that urges us to reflect and act on the world when we try to observe it from above when leafing through the pages of the renaissance atlas of Abramo Ortelio, or pondering The Blue Marble, the first photograph of planet Earth taken from the lens of the astronauts of Apollo 17. A geography that multiplies its potential every time an artist decides to partake in a dialogue with a geographic map – and the exhibition displays geographic rugs and a number of works by contemporary artists.

But most of all it offers the opportunity to consider another geography, that is able to teach us to know places through an uninterrupted dialogue with the historical processes and to persuade us through the example of two authoritative pieces of evidence dating back by a century, geographer Cesare Battisti and historian Gaetano Salvemini, that «there are no natural political borders, because all political borders are artificial, meaning that they are created by the conscience and will of man».

The set-up created by Fabrica is an experiential journey, on the discovery of the various geographical maps and the places that inspired them, through the creation of areas that urge visitors to follow them and interact with them. Elements with a linear and clean design, minimalist to focus solely on the works on display, combined with a graphic design that reinterprets the elements of traditional cartography in a modern style.

The entire design of the exhibition – set-up and communication – is combined with the spaces of Palazzo Bomben, rich in frescoes and history, in a dialogue of mutual accentuation.

The event, funded by the Regional Government of Veneto, in accordance with regional law 11/2014, art. 9, as part of the programme commemorating the centenary of the Great War.